News Media, Chattering Classes, and the Phantom Public

Let me “unload” more than a bit with a longer-than-usual introduction to this thematic section of my website, including its pieces about what’s happening to the American public sphere in which I’ve worked (and which I’ve criticized) for decades.

American newspapers began dying years ago, not mainly because of the sins of journalists (although there are plenty), but owing to seismic shifts in technology, ownership, marketing, reader demographics, and the civil society from which journalists come and which we claim to strengthen even when we’re also serving ourselves. The shifts I’ve just mentioned are transforming civil society and “the public” into a kaleidoscope of fragmented consumer audiences, assembled and dis-assembled by media corporations on whatever pretexts — ideological, religious, erotic, or nihilist — will draw more consumers’ eyeballs and, with them, advertisers, and, with them, bigger profits and shareholder dividends.

As publishers and editors dumb down the news or tart it up on such pretexts, newspapers and news programs come to deserve the deaths they’ve been dying through no fault of their own. “Democracy Dies in Darkness,” warns The Washington Post, owned by Amazon founder and outer-space bounder Jeff Bezos. But democracy dies also in a deluge of glaring, cacophonous messages that treat citizens as impulse-driven consumers or worse. “The challenge of journalism is to survive the pressure cooker of plutocracy,” said Bill Moyers — who began his adult life as a Baptist minister, became Lyndon Johnson’s press secretary, and has been a true practitioner of journalism as a civic craft — in his acceptance speech upon receiving the Helen Bernstein Book Award for Excellence in Journalism, at The New York Public Library in 2015.

Journalism is the only private industry named (as “the press”) in the U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment, which was written to protect self-governing citizens from repression by government. But the arts and disciplines of self-government need protection also from business corporations that have become almost as powerful as governments and often even more so. “The press” itself — including digital speech platforms — is still housed in media corporations whose main interest is not to enlighten a deliberating public but to assemble and dis-assemble mere audiences in whatever way will boost profits most quickly. That’s their main incentive, even (and sometimes especially) when it makes public life go badly in ways that bypass our brains and hearts on the way to our lower viscera and our wallets. Impulse buying, not civic strength, is most of corporate journalism’s Holy Grail.

Under such conditions, government censorship in America is less dangerous to good journalism than what media critic John Keane calls “market censorship,” the profit-crazed abduction of journalists from serving “the public’s right to know” to “giving the people what they want,” instead. This is done by following a perversely uncivil model of what many of “the people” can be groped and goosed into wanting — including wanting to be lied to with simplistic but comforting fables about who to blame for their unhappiness and who to follow to “fix it.” In speech platforms like Facebook, the public’s right to know is effectively market-censored by feedback loops of conspiracy-mongering, bigotry, and worse.

Partly that’s because platforms like Facebook insist, and market-worshipping jurisprudence affirms, that The First Amendment protects not only individual citizens’ right to stand against a stampeding herd but also media managers’ “right” to be mindlessly herd-driving and money-grubbing, in ways and for reasons I present in the following pieces. Fable-spinners on Fox News or MSNBC have ideologies, not just market interests, but, as Eric Alterman showed scathingly on his site “Altercations,” at The American Prospect, even “mainstream” news organizations such as CBS News (whose former chairman Les Moonves said that Trump’s rise “may not be good for America, but it’s damn good for CBS”) hire professional liars as on-air news analysts.

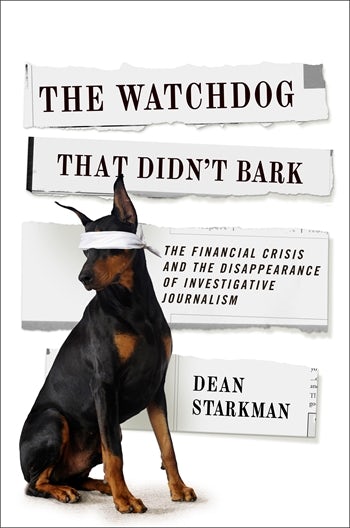

Digital social media have accelerated and intensified the deluge of misinformation and disinformation, as Richard L. Hasen explains well in a column that also recommends necessary legislative, jurisdictional, and civic curbs on a lot of what passes for “free speech.” But it’s equally true that the deluge of deception has been decisive ever since the emergence of mass-circulation daily newspapers in the 1890s. The Spanish-American war of 1898 and the grip of McCarthyite anti-Communist hysteria on American politics in the mid-1950s are only two examples of how the supposedly venerable gate-keepers of honest media misled readers and betrayed democracy itself. (See my Washington Spectator essay, re-published by Newsweek, “Don’t Blame Social Media for Fake News. Mainstream Media Got There First,” and my review of Dean Starkman’s book (pictured at the top of this section), The Watchdog That Didn’t Bark.)

This is a tragedy in the classical sense that tragic figures — in this case, publishers, editors, and a few too many reporters — hasten their doom by the ways they’re trying to escape it. We need journalists who are paid well enough and protected well enough from market pressures to keep on telling “the public” not user-friendly lies that keep people reading and watching for all the wrong reasons, but hard truths that uphold the civic-republican fairness and accuracy which business-corporate moguls and their bureaucracies can’t be trusted to sustain, any more than corrupt governments can be trusted to sustain. No state-directed or market-driven or bureaucratic-corporate model can substitute for the skills, resources, courage, and public trust that make journalism fair, accurate, and essential to freedom. If myopic jurisprudence and shareholder-driven priorities deplete those skills, resources, and trust while handing huge megaphones to corporations that leave civic-minded citizens with laryngitis from straining to be heard, then Trump was right: Too much of what Facebook and CBS News present as news is “fake.”

Although I was a student co-editor of my high school newspaper in 1964 and will always be grateful to its faculty advisor, John F.X. Lynch, for teaching me good values and habits, my journalism began in earnest in the mid-1970s, when I was in my mid-20s and newspapers were still trusted as carriers of democratic hope. From the civil-rights movement’s finest hours in the early 1960s through the Watergate exposes of 1973, more than a few journalists and news organizations stood tall as tribunes of the public, as trusted resources for citizen vigilance against elected officials’ and business leaders’ mishandlings of public trust. Televised imagery of civil-rights demonstrations and the Vietnam War, produced and presented by practitioners of journalism as a civic craft, pierced through fogs of official rationalizations and lies.

When such journalism exposes public corruption and private “special interests” that are hobbling popular sovereignty, it also exposes, indirectly but inevitably, some publishers, editors and reporters who’ve become sycophants to the established, corrupted forces whose investors’ interests effectively run their news organizations and platforms. Trump knew that a lot of “news” was “fake” in that way because it takes one to know one. But many Americans know it, too, only because they haven’t been seduced into the networking and pirouetting that market censorship demands of many of the journalists it hires.

In the 1970s, journalists and readers who were still independent minded and “civic” supported “alternative” newspapers and magazines that provided critical information and civic-republican clues missing from most mainstream media. I remember rushing to newsstands in Boston and New York on Wednesday evenings or Thursday mornings in the early 1970s to buy copies of The Village Voice as it tumbled off delivery trucks, bearing exposes of wrongdoing unearthed by muckrakers Jack Newfield and Wayne Barrett and scathing critiques of journalism itself by Alexander Cockburn in his “Press Clips” column.

In 1982 I was thrilled to become one of them, a writer of Voice exposes and interpretations, after doing something similar for The Harvard Crimson (where I met the future national journalists Nicholas Lemann, Jonathan Alter, and others) and for The Boston Phoenix, where Joe Klein, Sidney Blumenthal, Janet Maslin, and other national journalists also got their starts, thanks to The Phoenix’s editor, Bill Miller. Later, when I worked for daily newspapers in New York, I owed a lot to the wise, principled guidance of publishers such as Steven L. Isenberg and editors such as James Klurfeld and Anthony Marro at Newsday. (A few of my Voice, Phoenix, Newsday, and Daily News pieces are on this site’s sections, “Leaders and Misleaders” and “Scoops and Revelations.”)

Since the 1990s, editors and writers at websites, such as Salon editors David Daley and, now, Andrew O’Hehir, have fused wise public judgment with passionate advocacy, without descending into ranting or propaganda. Non-profit, online community journalism has been vindicated in New Haven, Connecticut, Yale’s hometown, by Paul J. Bass, founder of the New Haven Independent.

Another public practitioner of journalism as a civic craft who reaches beyond the class-bounded interests of corporate reporters is Alissa Quart, who directs the Economic Hardship Reporting Project. This non-profit journalism organization that covers inequalities of social class that so often exclude actual voices and perspectives of daycare providers, gig workers, opiod addicts, homeless people, and even labor and community organizers from most reportage and commentary. Even when such people are quoted or depicted by Ivy League reporters who’ve never really been Squeezed in ways that Quart describes in her book by that title or Bootstrapped in ways she discusses in her forthcoming book, they need to and can participate in the practice of journalism itself as a civic craft. Quart makes that case also in her Columbia Journalism Review essay, “Let’s make journalism work for those not born into an elite class.”

Alissa Quart Alchetron, The Free …alchetron.com

When digital production began to run circles around established journalism, many observers celebrated the Internet’s instantaneity and interactivity as the liberation of news gathering and commentary. But journalism’s essential (and classical) virtues — of courage, persistence, creativity, and tough-minded, public-serving optimism — can be short-circuited and misdirected if journalists have ingested the steroid of profit-crazed, tech-driven sensationalism.

As the alternative models that I’ve just mentioned have struggled and sometimes prevailed, rising practitioners like Bass, O’Hehir, and Quart and veterans of print journalism’s supposed glory days have watched the souffle-like collapse of many proud dailies into witless titillation machines chained to conglomerate bean counters. We’ve also experienced the corporate consolidation and co-optation of alternative weeklies and websites. The challenges to all news organizations aren’t coming only from the deluge of tech-enabled, unfiltered, self-indulgent, ignorant, and anti-civic clickbait. They’re essentially corporate, coming from media executives’ and managers’ obsession with boosting their own and shareholders’ dividends in whatever ways will glue customers’ eyeballs to their screens and pages and to advertisers’ come-ons.

Publishers’ and editors’ political priorities, too, may hobble a website’s fairness as decisively as they do a print publication’s, (For example, another thematic section on this website, “Israel’s Tragedy, America’s Folly,” presents the texts of columns that I wrote for Talking Points Memo between 2007 and 2010, but those columns disappeared — along with other TPM columns about Israel by M.J. Rosenberg and Bernard Avishai. TPM founder and editor Joshua Micah Marshall proved unable or unwilling to restore or to account for these disappearances.)

Any newsroom can be a hothouse-cum-snake pit of frazzled journalists who are competing with one another as often as they’re collaborating. That was as true at many of the old print-newspapers as it is at many news outlets now. But many people became journalists in the first place back then not just to see their own names in print but to master what the media critic Jay Rosen, in What Are Journalists For?, describes as a civic craft that helps to make public life go well by strengthening public vigilance and intelligence, not paranoia and ignorance.

Along with Paul Bass in New Haven, another master and eloquent defender of this civic craft is Dean Starkman, a former Wall Street Journal reporter who meticulously, fairly documented the American business press’ failures to report the oncoming train wreck of the 2008 national financial meltdown. Dean told hard truths about those failures, writing as a managing editor for the Columbia Journalism Review, where I first read him. He told those truths again in The Watchdog That Didn’t Bark, which I reviewed for Dissent magazine under a headline, “Reporting for the Republic”.

I hosted Dean Starkman at Yale, as I did Paul Bass, in my seminar on “Journalism, Liberalism, and Democracy” and, with Dean, at a class of future business leaders at the Yale School of Management. He shared his understanding of the difference between “accountability” journalism, which requires dogged investigation of entities that don’t want to be investigated, and mere “access” journalism, in which reporters expend too much of their talent on stroking powerful hands that feed them stories that are marketable but unenlightening. Dean has since worked with The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, which carries accountability journalism far and wide.

No one intuited the priorities of profit-chasing news organizations better than Ronald Reagan, who built his political career partly by playing self-righteously on journalists’ weaknesses even while castigating ratings-obsessed media for taking the bait of sensational-sounding stories that “sell papers.’ Here’s Reagan, talking with some of my Yale classmates in 1967, blaming journalism for distorting public understanding in ways that he himself had been distorting it since the 1940s. Both Reagan and the press were equally to blame for this dance of the damned. The same was true of Trump and the press decades later.

Can journalism as a civic craft outrun this circus? The newspaper columnist Walter Lippmann doubted that it could, explaining, as early as the 1920s, why mass media were unlikely to generate anything more than “manufactured consent” from a busy, distracted, and often gullible “buying public.” The challenges facing public truth are much older and deeper than those driven by manufacturing and buying. I can’t resist citing Edward Gibbon’s The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire to convey my apprehensions about what has become of American journalism since the end of the Cold War and of the relatively egalitarian material opportunities that had followed the victory against fascism in World War II. Gibbon could have been anticipating our condition now when he wrote that:

“This long peace, and the uniform government of the Romans, introduced a slow and secret poison into the vitals of the empire. The minds of men were gradually reduced to the same level, the fire of genius was extinguished…. [T]hey no longer possessed that public courage which is nourished by the love of independence, the sense of national honor, the presence of danger, and the habit of command…. The most aspiring spirits resorted to the court or standard of the emperors; and the deserted provinces, deprived of political strength or union, insensibly sunk into the languid indifference of private life.

“… A cloud of critics, of compilers, of commentators, darkened the face of learning, and the decline of genius was soon followed by the corruption of taste. The sublime Longinus… laments this degeneracy of his contemporaries…. ‘In the same manner,’ says he, ‘as some children always remain pygmies, whose infant limbs have been too closely confined, thus our tender minds, fettered by the prejudices and habits of a just servitude, are unable to expand themselves, or to attain that well-proportioned greatness which we admire in the ancients.”

Gibbon had his own 18th-century political agendas and prejudices. But several founders of the American republic had read him before they wrote the Constitution, so they knew that a polity needs to guard against slow and secret poisons. What they didn’t reckon with effectively was the reality that only some of those poisons come from government and that they aren’t slow or secret. Here are my accounts of some of the consequences.

A creeping coup, a sleeping news media

“Manufactured Consent,” The Washington Monthly, March, 2001. American news media’s mishandling of the 2000 election and of the prospects for responsible civil disobedience at that time.

This ‘Free Speech’ Crusader Won’t Tell a Certain Truth. Greg Lukianoff, a former First Amendment lawyer and now president of the right-wing funded Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, tells plenty of truths about suppressions of liberals’ as well as conservatives’ freedoms of speech. But his organization, the FIRE, has a skewed agenda that I made clear some years ago in reports, including a column I wrote for The New York Times, that prompted Lukianoff to accuse me of lying and ranting. Read this, and judge for yourself!

NY Times Reporters Lost a Connecticut Senate Race, Even Though ‘Their’ Candidate Won, Nov. 4, 2006. Ned Lamont (later Connecticut’s governor) was running against Sen. Joe Lieberman partly to protest his support for the Iraq War. NYT reporters had gotten a bit too comfy with folksy Joe, and it showed in their journalism.

What Leon Wieseltier’s Fall Showed About Washington’s Chattering Classes, AlterNet, Nov. 2011. For one thing, it revealed that they take war-mongering like his less seriously than groping. Wieseltier wasn’t wrong to warn that sometimes liberals must take up the gun and fight, but he was wrong to live for and in those times. Washington didn’t notice or object. His mild, mannered sexism mattered more.

“Enough With the F***ing Rich Kids.” The tragedy of The New Republic in 2012-2014, when it was owned by Chris Hughes, a wunderkind of commodification. Salon, December 9, 2014. Hughes and his kind didn’t misread what journalism, politics and capitalism in America are becoming. They read it only too well. Like so many other young, market-molded Americans, they don’t understand how the perversion of public life by tsunamis of marketing, financing and technological innovation has overwhelmed thoughtful writing, reading and the habits of mind and heart that sustain republican deliberation and institutions. (I don’t suggest that The New Republic was a better champion of America’s civic-republican ethos when it was owned by Martin Peretz, even though I wrote for it (and “around” Peretz’s prejudices) then.)

Rupert vs. the Republic

Between June, 2007, when Rupert Murdoch’s bid to buy The Wall Street Journal from Dow Jones was briefly in doubt — and August, when it became clear that he would take possession by the end of the year — I wrote four columns cautioning, cajoling, assailing, and ultimately despairing of journalists who were becoming Murdoch’s apologists.

Should American Journalism Make Us Americans?

I wrote this Discussion Paper for Harvard’s Shorenstein Center for the Press, Politics, and Public Policy when I was a fellow there in 1998. In it I argue that conglomerate news media are more interested in niche marketing to new immigrant groups than in guiding and prodding the newcomers toward full citizenship. It’s as if corporate bean-counters have displaced civic leaders at the helms of these news organizations, letting down immigrants by lavishing upon them the soft bigotry of low expectations of them as citizens. To understand what’s at risk for the country, read this account of how news organizations sometimes welcomed — and challenged — immigrants more constructively and less opportunistically on bottom-lining terms than they do now.

Liberals color the news, and conservatives lie about it openly

In 2002, reviewing William McGowan’s book Coloring the News, in which he challenged corporate newsrooms’ cookie-cutter, “diversity”-driven coding of hiring reporters and assigning them stories unofficially but effectively by race-and surname, I endorsed many of McGowan’s criticisms but cautioned against overdoing them. In 2011, he really did overdo them in Gray Lady Down, his conservative-funded, ideologically driven attack on the admittedly flawed New York Times, prompting me to take down his take-down, not so much to defend the Times as to defend journalism more broadly against what I characterized as ‘ressentiment’ that was insinuating itself into reporting and commentary.

(An editor at the Columbia Journalism Review called other journalists’ attention to my warnings. As it turned out, George Soros and I were saying very similar things at that time about the public sphere’s vulnerabilities.)

Exposing a columnist’s primary colors.

Memory and judgment, not “proof,” led me to decide in 1996 that Joe Klein, a prominent columnist and TV pundit, was also Anonymous, the unnamed author of the novel Primary Colors, a roman a clef about Bill Clinton and his circle. I first identified Klein that way to William Powers, the Washington Post’s media columnist (the relevant column is the second item on this pdf). In a subsequent column of my own, I insisted on the validity of my finding, even though most journalists still accepted Klein’s vehement denials that he was the novelist. I couldn’t persuade anyone to publish yet another column of mine that began, “May I remind Joe ‘I didn’t do it’ Klein of O.J. Simpson’s vow that he will ‘leave no stone unturned’ until he finds Nicole Brown Simpson’s killer?…. If Klein didn’t write Primary Colors, let him devote his far-more-considerable investigative skills to finding its author.”

Only when another reporter discovered a paper manuscript of Klein’s novel with his own handwriting on it did Klein confess vindicating my claim. Why had I been so sure of his authorship, despite his denials? Having read and admired many of Klein’s columns in New York magazine in the late 1980s, I hadn’t forgotten his characteristic locutions and obsessions about liberals and race. So I noticed them when some of them popped up in the novel — as, for example, when he punctuated his account of some politically correct absurdity by writing, simply, “Yikes!” Then I saw a column in the Baltimore Sun by David Kusnet, a former speechwriter for Bill Clinton, that expressed similar suspicions, so I read Klein’s novel again and more of his locutions leapt off of its pages. It was then that I called the Post’s Powers, who wrote about the “Kusnet/Sleeper theory” of authorship. That prompted Klein to leave me an exasperated voice-mail message: “Jim, I don’t have a patent on the word ‘Yikes’!”

Well, maybe so. We were in a gray area, where I “knew” a truth in my bones thanks only to good memory, some literary acumen, some political judgment, and some circumstantial evidence. When Klein finally told the truth at a press conference with the novel’s publisher, Random House’s Harry Evans, I faced him wordlessly from the crowd of reporters. And, in a Wall Street Journal column (linked here with the Powers column), I offered my interpretation of why he’d lied so vigorously, and at what cost to journalism and politics.

In Washington’s punditocracy, ‘status’ is achieved at the unspoken cost of self-esteem. If you want to present the whole truth in primary colors, you may also want to be anonymous.

An early storm warning about moralism and arrogance

Also in the realm of predictions based on memory and judgment, I wrote somewhat nastily about journalism itself for the first time in a Daily News column in 1994, predicting that the New York Times’ then-editorial-page editor Howell Raines would cause problems for the paper and journalism generally. I said it again at length in 1997 in Liberal Racism, in the chapter called “Media Myopia.”

But not until 10 years after my News column was Raines brought down, partly by the scandalously false reporting of a young Times reporter, Jayson Blair. Raines is a great journalist with great flaws, including but not limited his a penitential Southern anti-racism that can get so tangled up in itself that it clouds realistic judgments upon which true justice always has to rely.

By the time of Raines’ editorial demise in the Blair affair, I was no longer at the Daily News but couldn’t resist writing an “I told you so” column in the Hartford Courant (it comes after the Daily News column in the link above) that was widely linked and reprinted. It even wound up in The Jerusalem Post, edited at the time by Bret Stephens, whose neo-con’ish, McGowan-like inclinations inclined him to highlight a crisis at a liberal newspaper such as the Times – which later hired Stephens, when it was running scared of conservative competitors.

I’ve defended and even celebrated Times writers and editors who’ve kept the better, harder faith. See “Who Needs the New York Times? We all do. Still.” It ran in TPM and was read widely by journalists at the time, but it was one of a raft of columns by me and other contributors that disappeared from that website.

The cheapest kind of flattery

Commentaries that break new ideas rather than news are more easily stolen that news itself. Not long after I’d written this Washington Post review of Marshall Frady’s biography of Jesse Jackson, 18 paragraphs of my review wound up under someone else’s byline a few weeks later in the San Francisco Chronicle. The reasons were instructive, if depressing. My Hartford Courant column reflecting on them, partly in light of the Jayson Blair debacle, is the second column on this pdf.

Running scared of right-wing “noise”

When New York Times publisher Arthur Sulzberger Jr. hired the neo-conservative field marshal and propagandist William Kristol as an opinion-age columnist in 2007, I sensed that Sulzberger was running scared of The Wall Street Journal’s new owner, Rupert Murdoch. Certainly the Times needed sharp conservative commentators who can keep-liberal readers on their toes, but Kristol was the opposite of sharp, and his tenure there was mercifully short. Bret Stephens is much sharper than Kristol was, but no less propagandistic. Ross Douthat is more broad-ranging and engaging there, but he’s so often obsessed with blaming social ills on liberal domination that I diagnosed him for the History News Network as a walking casualty of IDS — Ideological Displacement Syndrome.

Book reviewing as ideological policing

The journalist Nicholas von Hoffman once told me that he’d given up reviewing books because he’d decided that “It’s not worth $250 to make an enemy for life.” Even just assigning and editing other writers’ book reviews can earn book-review editors some enemies for life, and that danger inclines some editors and some favored, “reliable” reviewers to cozy up to one another in unspoken ways, when it comes to picking and choosing their prospective battles “safely” as books and reviewers are assigned. Some book-review sections come to resemble clubhouses or royal courts, in which editors bestow assignments on reviewers who anticipate and follow their preferences instead of ruffling their feathers. Is the author of a book that’s being considered for a review “in good odor” with the review editor? is the author acceptable ideologically? There are fairer ways to assess a book’s merits and to assign reviewers to assess them. But some editors decide on the basis of the narrower inclinations and prejudices that I’ve just mentioned.

I exposed such difficulties in this 2007 Nation magazine broadside against The New York Times Book Review, which, under editor Sam Tanenhaus, a self-described “sympathetic observer” of conservatism, was running a steady stream of negative reviews of books by critics of the Iraq War from 2003 to 2007, as the reality of America’s grand misadventure there was moving from triumphal to inexcusable. One day I told Tanenhaus’ deputy editor Barry Gewen that the NYTBR had become “a war-hawks’ damage-control gazette.” Even a publication with a broad reach and civic mission will have some distinctive editorial preferences (and strengths and weaknesses), but my Nation piece showed pretty damningly that the Times had gone too far in favor of excusing the war and bashing its critics. By showcasing pro-war reviewers such as Christopher Hitchens, Richard Brookhiser, Paul Berman, Peter Beinart, and David Brooks, the NYTBR fed public antipathy to presumptively feckless opponents of the war.

In The Guardian, in 2007. I assessed editor Tannenhaus’ writerly and political record. Not long afterward, the NYTBR seemed to adjust its course in a special issue on politics, publishing a better mix of reviewers of non-fiction, political books. At that time, I wrote a column acknowledging what seemed a welcome shift in the section’s balance. But, even as late as 2009, deputy editor Gewen, who had essentially assigned and edited the Iraq War reviews, hadn’t let go of his own inclination to skew them in favor of the war. Eventually I reported, in this 2020 review for The New Republic of NYTBR deputy editor Barry Gewen’s intellectual biography of Henry Kissinger, that although Tanenhaus was ultimately responsible for assigning books to reviewers, the books whose reviews I’d assailed had indeed been previewed and selected by Gewen, who had edited all of those reviews. (He edited some of mine on subjects unrelated to foreign policy in the 1990s, such as the pitfalls in American multiculturalism, and such as conservative mis-readings of Allan Bloom in their attacks on universities. But, during the Iraq War, we went our separate ways.)

Where to?

Given how I’ve spent the last 40 years, I plead guilty to having expected more of journalism than it can deliver on its own. But in the next thematic section, “Scoops and Revelations,” I recount some of my journalistic triumphs that I dare say did help to make public life go well.

Ultimately, journalists draw upon and reflect the strengths (and weaknesses) of the deeper (or shallower) civic culture that they serve (or dis-serve). “The public’s right to know” can become a meaningless slogan for journalism’s mission if the public is demanding to be lied to because millions of its members are stressed and dispossessed enough to crave simple directions for scapegoating others and following Leaders. When Trump called journalism “fake news,” he was anticipating bad journalism’s acceleration of such desperation.

But journalism fails that way only after subtler poisons have stupefied its readers and viewers. For that, I blame the deluge of commercially over-determined, algorithmically driven, hollow “speech” by conglomerates, only some of which are in the business of journalism itself. I’ve outlined this challenge in the essays “Speech Defects,” in The Baffler, and “How Hollow Speech Enables Hostile Speech,” in The Los Angeles Review of Books.