Yankee Doodle Dandy

Los Angeles Times Book Review

July 2, 2000

Norman Podhoretz’s My Love Affair With America is mainly about making it in America while breaking ranks and settling scores.

By Jim Sleeper

The truculent conservative writer and editor Norman Podhoretz “did not… fight his way out of ‘political leftism’ to abide ‘the anti-Americanism of the Right,”‘ writes Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan on the cover of this new book; “It is America he loves, not ideology.” Thus encouraged, any reader might well open “My Love Affair With America” expecting to hear a voice of civic conscience that has been missing in this country’s ideologically riven, and increasingly inane, politics. Having broken ranks with what he called the “hate America” left in the 1960s and ended up on the right, mightn’t Podhoretz indeed break ranks again, this time to strengthen an America that has made amply, if quietly, clear since the Clinton impeachment effort that it loathes ideologues on both sides of a discredited divide? To appreciate what a let-down Podhoretz’s book actually is and why that matters, it helps to know what besides Moynihan’s encouragement might have raised expectations in the first place.

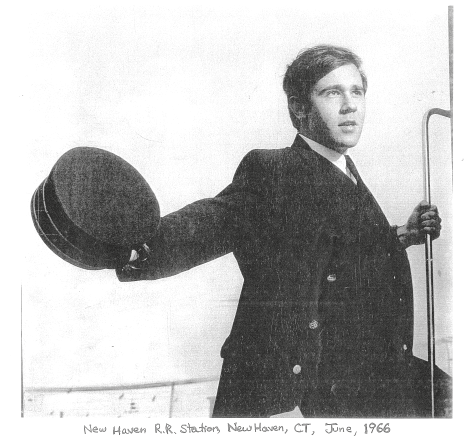

The Podhoretz who decamped prophetically, if bombastically, from liberalism had begun his career as a public intellectual with the credibility of a poor boy from immigrant-Jewish Brooklyn who’d made what he called “the brutal bargain” of assimilation to Western high culture on scholarship at Columbia University and Clare College in Cambridge, England. It had been brutal, he reported, because to be accredited one had to have cut off one’s proletarian roots. Podhoretz had done this but not without misgivings laced with muted shame: He would recall years later that upon ascending to Cambridge at 19, he was ushered into the first bedroom he’d ever had to himself, where, as the door shut behind him, he burst into tears.

Winning distinction as a student and critic just as American liberalism strode forth to change the country and the world, he found he had license to renegotiate the deal he’d made with high culture at Brooklyn’s expense. As the new, young editor of Commentary magazine after 1960, he mid-wifed a then-unknown Paul Goodman’s “Growing Up Absurd” and introduced liberals to James Baldwin, who was writing “The Fire Next Time.” In 1965, he published the civil rights leader Bayard Rustin’s argument that although black riots in Watts and other urban ghettoes were immorally and self-destructively violent, they were tortured calls for what amounted to democratic socialism.

At the same time, however, Podhoretz helped spark a role reversal in how conservatives and liberals would address race. The former had long said, in effect, “Every group in its place, with a label on its face,” while liberals had fought to transcend race legally and even culturally. Podhoretz’s 1963 essay, “My Negro Problem–And Ours,” was the much-noted bellwether of the coming conservative rebellion against a patronizing, race-drunk liberalism. Although the essay (reprinted most recently in Paul Berman’s anthology “Blacks and Jews”) ended with a then-characteristically liberal call to transcend race through miscegenation, it unloaded a quiver of barbed, proletarian truths, drawn from Podhoretz’s recollections of growing up among poor blacks, that punctured some hot-air balloons of liberal optimism about busing and other racially obsessed, quick-fix, “integration” schemes then floating across the land.

A few years later, he would help conservatives claim that in a true free-market society, the only color that mattered would be dollar green; it was liberals, he charged, who were squandering the civil rights movement’s moral capital by advocating racial preferences and other social color-coding that abdicated the struggle to rise above race.

Podhoretz was a bellwether in other ways, as well. In 1966, he edited “The Commentary Reader,” whose more than 50 essays confirmed the magazine’s acuity and sheer range of well-grounded interests. Because many of the essays had appeared before Podhoretz was editor, he rightly credited his predecessor Elliot Cohen with “an uncanny sensitivity to what may be called the representative issues–that is, the problems preying on the minds of a great many people at a given moment . . . he invariably knew where the relevant areas of discussion lay and by which writers they might be illuminated.” Podhoretz could also quite rightly have written the same about himself.

Not quite so rightly, he did just that a year later, in “Making It,” a premature memoir-cum-advertisement for himself whose purported revelations about New York literary life angered many of his admirers. “Making It” virtually celebrated what Cohen’s work had seemed to discredit: the “dirty little secret,” as Podhoretz called it, that every American writer lusts after fame, fortune and power and lies about such desires. Chronicling his own literary ups, downs and apercus with the self-infatuation of an infant discovering his toes, Podhoretz seemed to expect the kind of adoration he’d gotten from his mother and her friends. Instead, he was dismissed by “the family” of New York intellectuals who’d admitted and even anointed him a promising young critic only a few years before.

Podhoretz emerged from what he considered New York liberals’ mug and hypocritical disdain with 20-20 foresight about their conceits and a rage to drive home hard truths they’d suppressed. He would keep his “brutal bargain” with high culture by acknowledging the importance of ambition and political power. They would continue to betray the bargain, not least by disguising their own ambitions with support for “the oppressed,” whose lives he understood far better than they. For the next three decades, Podhoretz would cry that his liberal ex-friends were betraying ordinary Americans’ best hopes by indulging fantasies of Third World revolution and by romanticizing, then institutionalizing, racial and sexual identity politics that cheat their intended beneficiaries while projecting the intellectuals’ own thwarted power lusts. They were wrecking an America whose prosaic capitalist and constitutional strengths had liberated more people than all “progressive” efforts combined.

Podhoretz has kept demanding vindication of his claims so obsessively that he’s nearly made himself the Rodney Dangerfield of public intellectuals. “My Love Affair With America” is his fourth book about his conversion from liberal pietism to self-proclaimed defender of the American Truth. (The others, after the clamorous “Making It,” were the bitterly tendentious “Breaking Ranks” in 1979 and the endlessly self-justifying “Ex-Friends” in 1998.) Increasingly, and not a little vindictively, he has always counterposed his new political family of the “patriotic” right to the “hate America” left.

But now such distinctions are blurring in another great role-reversal, this one involving conceptions of American national identity itself. And Podhoretz seeks to be prophetic again, this time against an anti-Americanism among his friends on the right that, mirabile dictu, bears an unnerving resemblance to what he denounced on the left. In this book his warnings are less credible, though, because over the years he has let the enemies of his old liberal crowd become such good political “friends” that he’s in harness to their conservative movement, however uneasily. This matters, because the devil’s bargain he made with the right out of disgust for the left is typical of many ex-liberals who followed him. Yet it would be unwise for liberals to gloat over the many false notes and incoherencies in “My Love Affair With America.” The book is a sad testimony to how an ideological temperament, no matter what its doctrine, drains the political culture it claims to advance and saps the civic virtue of the ideologue himself.

II

Every month brings new indications of the nationalist role-reversal that is prompting Podhoretz’s unease: This year’s presidential primaries saw conservative leaders of a Republican Party long associated with a flag-waving patriotism scramble to discredit an American war hero who charged that a global capitalist “iron triangle” of big money, bad lobbyists, and undemocratic legislation is debasing his party and his country. Liberals, meanwhile, found themselves casting shy, admiring glances at John McCain’s insurgency: On National Public Radio, former Clinton Labor Secretary Robert Reich marveled that McCain had electrified apathetic citizens, many of whom didn’t want patriotism left to Pat Buchanan and Oliver North. In Seattle during the meetings of the World Trade Organization demonstrators protested the fact that Third World regimes oppose the very environmental and worker protections found in American laws. “Our country has many things well worth protecting, and most . . . are social inventions, not individual factories,” commented Robert Kuttner, editor of the liberal American Prospect. “If this idea makes me a protectionist, I wear the Made-in-USA label with pride.”

These aren’t stadium shouts of “U.S.A.!,” nor is there racism or imperialism in such stirrings of national pride. McCain tapped a hunger for what the philosopher Jurgen Habermas calls the “constitutional patriotism” of Americans who joined the civil rights and anti-war movements to oppose the government on behalf of an American civic nation transcending “blood and soil” and profits. Similarly but more recently, the philosopher Richard Rorty unnerved some fellow leftists by arguing, in “Achieving Our Country,” that national pride is as important to struggles for social justice as self-respect is, and that the left has abdicated its responsibility to keep American self-respect on the sound footing set by Eugene V. Debs, Franklin D. Roosevelt, A. Philip Randolph and others who were anything but conservatives.

What better time, then, for an ideologically conciliatory “love affair with America?” Surveying the ruins of a century’s world-saving schemes, Rorty, Michael Lind (in “The Next American Nation”), the historian Benjamin Barber (in “Jihad vs. McWorld”) the sociologist Seymour Martin Lipset (in “American Exceptionalism”) and others find the United States pretty exceptional, after all. Not that the country is divinely blessed or racially superior; it’s an extraordinary experiment in post-national civic nationalism, perhaps even in democratic world citizenship. The European Union is such an experiment, too. But the United States, founded on liberal Enlightenment terms and peopled too dynamically for ethnic corralling, has become the very progenitor of the very globalism and cosmopolitanism that nudged even the European Union into being. Our flaws are ghastly, yes; but compared to whom?

Another way of making the argument would be to show that even as global forces outstrip old national identities, we still need nations. Individuals can flourish only in societies borne of distinctive narratives, customs and principles–societies in which each of us has a voice and which sometimes we must be nudged, by law, to support. Because men aren’t angels, as James Madison famously warned, they need legal and civic structures strong enough to vindicate their rights against impassioned factions and to train the young in the arts and graces of public trust. Only civic nationalism can do that for populations as diverse as America’s. Ethnic, racial and religious sub-groups can’t. The European Union, the United Nations and the World Trade Organization can’t. That leaves American citizenship the promising microcosm of a larger world project: to nourish enough social benevolence and bonds across lines of race and class to offset self-fulfilling prophecies of group mistrust that rationalize all sorts of oppression.

Ideologues, by creating the “factions” against which Madison warned, deplete civic breathing space; the leftists among them sacrifice Madison’s constitutional balance to a “cosmopolitanism” so abstract it rationalizes global enterprises fleeing environmental and worker protections. Conservatives, defending even global investments that accelerate the social decay they decry, sacrifice Madison to Madison Avenue. Each side has fought the other to a sterile peace: The left has lost the economic wars to the right, and the right has lost the culture wars to the left, making the more fortunate among us the bourgeois bohemians of David Brooks’ recent “Bobos in Paradise.” Many Americans whose lives are less charmed are left with a sinking feeling that the old decencies driving the McCain and World Trade Organization insurgencies are little more than doomed, wistful gesturings of a lost civic love.

III

Over to you, Norman Podhoretz! Alas, “My Love Affair With America” is oddly esoteric and thin, or hopelessly self-referential, oblivious of recent discourse on America’s national identity. His acuity seems played out, and in its wake, there is only maundering: Every page or so, he changes the subject to follow some other old war story that has just occurred to him–and to duck a more important insight he’d rather not follow through.

Podhoretz opens (and closes) by remarking on an “outburst of anti-Americanism” among some conservatives whom he had thought were immunized against it. “I should have known better,” he writes, “than to be surprised, familiar as I was with the traditions on which the conservatives were drawing,” such as elitism, racialism, anti-Semitism, and some para-military or terrorist-like opposition to liberal constitutional government. Seeing all this, he recounts, “I fell into a despair . . . over the possibility that I was now about to earn myself a new set of ex-friends on top of the ones I had made thirty years earlier in breaking with the Left. Fast approaching the age of seventy, I was too old to seek yet another political home.” Fortunately, he claims, right-wingers’ “passions cooled” just as he wearily buckled on his armor to defend America again.

The truth, more likely, is not that Podhoretz’s right-wing allies calmed and redeemed themselves, or that he feels “too old” to seek another home, but that his enduring resentment of the left has driven him too much into the conservative movement to permit his discovery of the real, less-ideological, America. In this, he shares the sad fate of other northeastern Jewish intellectuals–Irving and William Kristol, Gertrude Himmelfarb and, in the younger generation, David Brooks and David Frum–who awoke amid the Clinton impeachment campaign to find themselves standing beside “blood and soil” mystics, racists, religious hysterics and aristocrat-wannabes, people as “un-American” as Communists were.

Alas for his colleagues’ enlightenment, Podhoretz relives personal triumphs and hurts as if they were templates of the national political culture. Only if you were his biographer or a literary historian would you want to know, for example, how his love affair with America was shaped and shadowed by reactions to a negative review he wrote, in Commentary, in 1953, of Saul Bellow’s “The Adventures of Augie March,” which Podhoretz’s liberal intellectual “family” saw as the first novel to stake a compelling Jewish claim to full American identity. For Podhoretz, “this unquestionably desirable, and even noble, project failed as literature because it was largely willed . . , not the natural, organic outgrowth of a state of being already achieved, but rather the product of an effort on Bellow’s part to act as if he had already achieved it.” Fair enough, perhaps, but do we really need a chronicle of every major literary figure’s whispered or imagined reaction to his review, and of Podhoretz’s reactions to the reactions, and of his second-guessing of even his supporters’ motives?

What drives these ruminations about everyone else’s past failures to celebrate them with full throats and whole hearts? Perhaps it’s Podhoretz’s discomfort at finding himself yoked, or at least driven, to do some of the right’s dirty work in punishing apostates like Michael Lind (who exposed conservatives’ enthrallment to televangelists) and Glenn Loury (who exposed their “Bell Curve” racism) with graceless “good riddances” and insinuations that amount to character assassinations. Podhoretz has done this, even though he knows far better than younger colleagues who behave similarly that, whatever the renegades’ eccentricities, many of their criticisms are as valid as any he made of the left.

Worse, he has fronted for positions that intellectual and moral integrity wouldn’t abide, and this, too, must have made him uneasy. For example, he keeps circling back to anti-Semitism, gently cautioning conservatives about it. But Commentary has temporized long and tellingly about anti-Semitism on the right, from penning tortuous apologias for Jacobo Timerman’s Argentine-junta tormentors to excusing the theocratic conspiracy theories of Pat Robertson, who so loves Israel that he wants American Jews to be there for Armageddon. Podhoretz would never explain away leftist anti-Semitism so sinuously. Surely, every Brooklyn Jewish bone in his body is telling him to slam anti-Semitism wherever it shows its countenance.

Podhoretz has fronted, as well, for a sham less dramatic but more dangerous: Some conservatives’ pretense that free markets alone liberate the country’s best strengths. He writes, fairly enough, that “radicals were being driven half crazy by the refusal of America in the 1950s to fulfill their predictions of a postwar depression that would generate a new wave of social protest and discontent.” But conservatives, driven even crazier by America’s refusal to rise up against Bill Clinton during the impeachment campaign, concluded that social decay and personal irresponsibility had gone farther than they’d realized. What they can’t conclude without the help of someone as perspicacious as Podhoretz is that moral decay has advanced behind their own corporate triumphs. For Podhoretz, racial preferences and group labeling are part of the decay of personal responsibility. Worse then is the fact that what had been a liberal agenda is now being usurped by CEOs. When, for example, Washington State’s 1998 referendum against public affirmative action passed, the big defenders of preferences were such capitalist combines as Boeing and Microsoft, a fact that made some on the left wonder whether the color-coding of American identity is really so “progressive” after all, and some on the right wonder whether private-sector bureaucrats can be just as stultifying as public ones.

In another circle of Podhoretzian hell, mass marketing has so shuffled our libidinal as well as racial decks that it’s comfortable peddling sexual degradation. The Calvin Klein-cum-kiddie porn ads that showed up a few years ago on New York City buses were put there by private investors in the free market not by liberals. Podhoretz says nothing about any of this. But if it’s wrong for the left to demonize as conspiratorial and even fascist the many mindless free-market disruptions of social life, it’s wrong for conservatives not even to question corporate priorities.

Podhoretz claims that he left the left for the right because he’d seen “radicalism” through to its ugly bottom. He says he was a “radical” and a “utopian” in the early 1960s, the unwitting bearer of a social “disease” whose flushes of apparent optimism conceal the carrier’s ripeness for disillusionment and then complicity in cruelty and oppression. He writes that he naively believed that America could end the Cold War and arms race, abolish poverty and racism, loosen and liberate sexual relations without destructive effects on marriage or the rearing of children (this is the closest the book comes to discussing the feminist movement) “and so on and so on into the blinding visions of the utopian imagination. . . . I was also convinced that all this could be done through reforms ‘within the system’ and without evolutionary violence.”

Never mind that because many intelligent people did believe such things, we’ve inched closer to realizing some of them. Did Podhoretz himself truly believe them? Not if, as he also writes, he was seduced by utopian siren songs into an “infidelity” to America that has required his “repentance,” a “painful self-examination of what it was in the ideas I had held and helped to disseminate that could have given birth to the monsters [of anti-Americanism] I now hated and feared.” Had this one-time disciple of Lionel Trilling and F.R. Leavis never considered Edmund Burke or Thomas Carlyle’s accounts of the French Revolution? Did he publish Goodman and Baldwin because he was naive, or because they rode the zeitgeist and he wanted to be “with it”? “A critic with a good pair of ears once wrote that he could hear in some of Podhoretz’s essays ‘the tones of a young man who expects others to be just a little too happy with his early eminence,”‘ he tells us. And, “I discovered that . . . the ideas we had been shaping and disseminating spread faster and further than I had ever dreamed possible” — even to the Kennedy and Johnson White Houses, he recounts. Nothing utopian there. Was Commentary, by any chance, being mailed to the West Wing from Podhoretz’s office?

Fortunately, he now says of such disseminations, “[T]here were protections in America against a seizure of power by utopians” such as himself. This would be comforting if there were no other evils or sicknesses imperiling America. But the most likely peril isn’t the left’s utopian-totalitarian impulses or the right’s fascist vagaries but the bread-and-circus decadence, reminiscent more of the late Roman Empire than of the Soviet Union or Nazi Germany, coming your way relentlessly via the tube, the Internet, the casino, the sex shop and now the psychiatric clinic, where even irreducibly moral crises are medicated away. It’s driven less by the left than by the quarterly bottom line and by the marketing division. Against this, Podhoretz’s protests aren’t even feeble; they’re non-existent. “The economic system [liberals] were denouncing was itself a form of freedom,” he writes. Calvin Klein is with him there.

There’s yet another cautionary tale in the book, this one for the chattering classes: While there are times for every new group and talent to make its noisy claim to American acceptance, a full love of a country or culture needn’t be “glorified with a full throat.” The Jews’ time to do that came (and went) in the first half of the last century with Mary Antin, Israel Zangwill, Emma Lazarus and Alfred Kazin, or, more uproariously, with Bellow and Norman Mailer. By now, more Jewish writers ought to have joined Lincoln in evoking mystic chords of a larger national memory and aspiration. The best such writing (Philip Roth’s “American Pastoral”, for example) is a dance of fewer words and more telling silences. Patriotic bombast and ethnocentrism cheapen civic love.

The literary historian Daniel Aaron describes three stages in the maturing of a fully American writer in “The Hyphenated Writer,” an essay in his collection “American Notes.” There is the outsider who demands acceptance of his or her group; the more confident interpreter who builds bridges between that group and others, in an idiom all can share; and the seasoned writer who makes a fully American, if ethnically inflected, contribution to some vision of the whole. Aaron is being diagnostic, not prescriptive, but it’s hard not to think of Podhoretz as stuck somewhere between the second and third stage, which “My Love of America” shouts he’s attained but which every passage, straining for vindication or ingratiation, shows he hasn’t.

Podhoretz knows this. Lamenting years ago, in “Making It,” that his “family” of Jewish intellectuals “did not feel that they belonged to America or that America belonged to them,” he fretted that their prose “had verve, vitality, wit . . . but rarely did it exhibit a complete sureness of touch; it tended instead to be overly assertive or overly lyrical or overly refined or overly clever’–unlike the writing of older-stock Americans such as Van Wyck Brooks and Edmund Wilson, whose “sense of rootedness gave a certain music to their work.” In the 1966 Commentary Reader, Philip Rahv warned that “any attempt to enlist literature in ‘the cause of America’ is bound to impose an intolerable strain on the imaginative faculty. Far better, Rahv argued, was quieter writing like the lovely closing paragraph of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby,” which, by allusion and understatement, traces the gossamer threads of bafflement, nostalgia and keening in Nick Carraway’s dreams of America.

What a long way from demanding that America be “glorified with a full throat and a whole heart.” If Podhoretz truly loves America, where’s his contribution to a common narrative? Why these endless, pointless recyclings of old miscommunications and affronts? Why can’t he make it to Aaron’s third stage?

The answer is clearest in his closing chapter, “Dayyenu American Style,” whose Hebrew word–“Enough for Us”–is the refrain of a Passover song affirming that any one of God’s many gifts to the Jews leaving Egypt would have been more than enough. In that spirit, Podhoretz means to count his blessings, but he begins by complaining that gratitude to America has been replaced by whining, citing “the ugly hostility” that greeted William F. Buckley Jr.’s 1983 memoir, “Overdrive,” in which the author surveys his opulence and feels “obliged to be grateful.” This prompts a digression of a couple of pages on Trilling’s misapprehension that conservatism like Buckley’s was a collection of “irritable mental gestures which seek to resemble ideas.” Next, Podhoretz returns to his theme of ingratitude: He touches on old-stock aristocrats’ alienation from a society that has sidelined them; the affinity between Southern agrarian conservatives’ resentments and what Podhoretz regards as Gore Vidal’s anti-Semitism; the difference between Richard John Neuhaus’ call for conservative non-compliance with immoral Supreme Court decisions and Podhoretz’s own strident anti-Court rhetoric (concerning racial preferences).

A reader wonders where all this is leading. So, apparently, does Podhoretz. Reviewing these contretemps, he sighs, “I was not about to make any predictions as to what lay in store for this country with which I was madly in love. Having entered even by today’s standards of longevity into old age, I found it, as the elderly always have, more comfortable (and less threatening!) to look back than to look ahead.” At last, he says what he’s grateful for–for the distinctively American philanthropic ethos that gave him scholarships, and, more profoundly, for “a system in which, for the first time in history, individuals were to be treated as individuals rather than on the basis of who their fathers were. . . .”

“I know, I know,” he adds defensively, “This principle was trampled upon by slavery…. There follows a new round of regrets about race and Vietnam, more pieties, and, “looking back as a septuagenarian on my life as an American, I am again reminded of something Jewish….” Funny thing; so am I. Over the centuries, the old refrain “dayyenu” has taken on an impish inflection–“Enough, already!”–as merry seder-goers tire of the liturgy and demand to eat. But Podhoretz can’t stop his recitation. He tells us that if America had given him only the English language, then dayyenu–that would have been enough.

Had it sent him to great universities in New York and England, dayyenu–surely that would have been enough. And on and on: his chance to mingle “with some of the most interesting people of my time”; to run a magazine with complete freedom for 35 years “even when I was spending ten of them ungratefully attacking . . . America itself”; his country home, where he is “writing these very words . . . behind an unpainted wooden door that . . . snaps shut with the very same satisfying click that so mysteriously broke the dam of tears in the nineteen-year-old boy I was more than fifty years ago.”

Dayyenu, Norman. Enough, already. It’s more than 30 years since you first wrote about those tears. One of your nemeses and a mentor of mine, the late Irving Howe, didn’t room at Cambridge or sup at its high tables, but when his garment-worker father’s union won a strike, there was meat on the family table in the Bronx more than once a week for the first time in years. Right though you are about some things Howe got wrong, why not thank an America where, even today, Los Angeles janitors have rights enough to stake their own modest claim on opportunity and where your fellow septuagenarians who couldn’t win Fulbrights had the GI Bill? One needn’t be a socialist to do that; a good civic Madisonian could. Open your door a little to an America beyond both ideology and egoism, and stop giving patriotism such a small, sad name.